Book Notes: The Internet is not what you think it is

A preface, a discussion, a review

Readers — since my last post five months ago, my wife and I welcomed a beautiful baby girl into our family. This has limited my writing time, and made my life immeasurably better. Children are wonderful.

Anyways, I’m starting to revisit my regular writing practice, but I don’t plan to post regularly for a while. I do plan, however, to start sharing short-form book notes here on Substack Notes, as a way to highlight interesting ideas, and to connect with anybody hanging out here.

What follows below are some such notes from

‘s The Internet is not what you think it is. If the book sounds interesting, check it out. Justin’s got some tremendous stuff here on Substack as well.I stopped reading philosophy several years back. In part I had more practical ways to fill my time. In part I had begun to fear works of philosophy, and the intellectual slogs they often became. Reading philosophy felt like distance running — I hadn’t even started by the time I was ready to quit.

I picked up The Internet is not what you think it is because I love

. But I soon realized this was a proper philosophy book written by a proper philosophy professor. Was my attention fit enough for this, especially after years of Slack and iPhone addling my brain?I need not have worried. The internet is not what you think it is reads more like a collection of Hinternet essays than a Kant-esque Critique of Pure Connectivity. Which is not to say it’s light. There’s a lot here — philosophy, history, social analysis, and personal reflection mix together. But novices like me can enter (and re-enter) it from any point without losing too much momentum.

Smith’s overarching thesis is that the internet is, in essence, nothing new. It is just the latest iteration in homo sapien's quest to world-build across time, space, and individuals. To support this, Smith employs genealogical analysis, or an examination of the history of the idea of the internet (rather than the history of the technology itself).

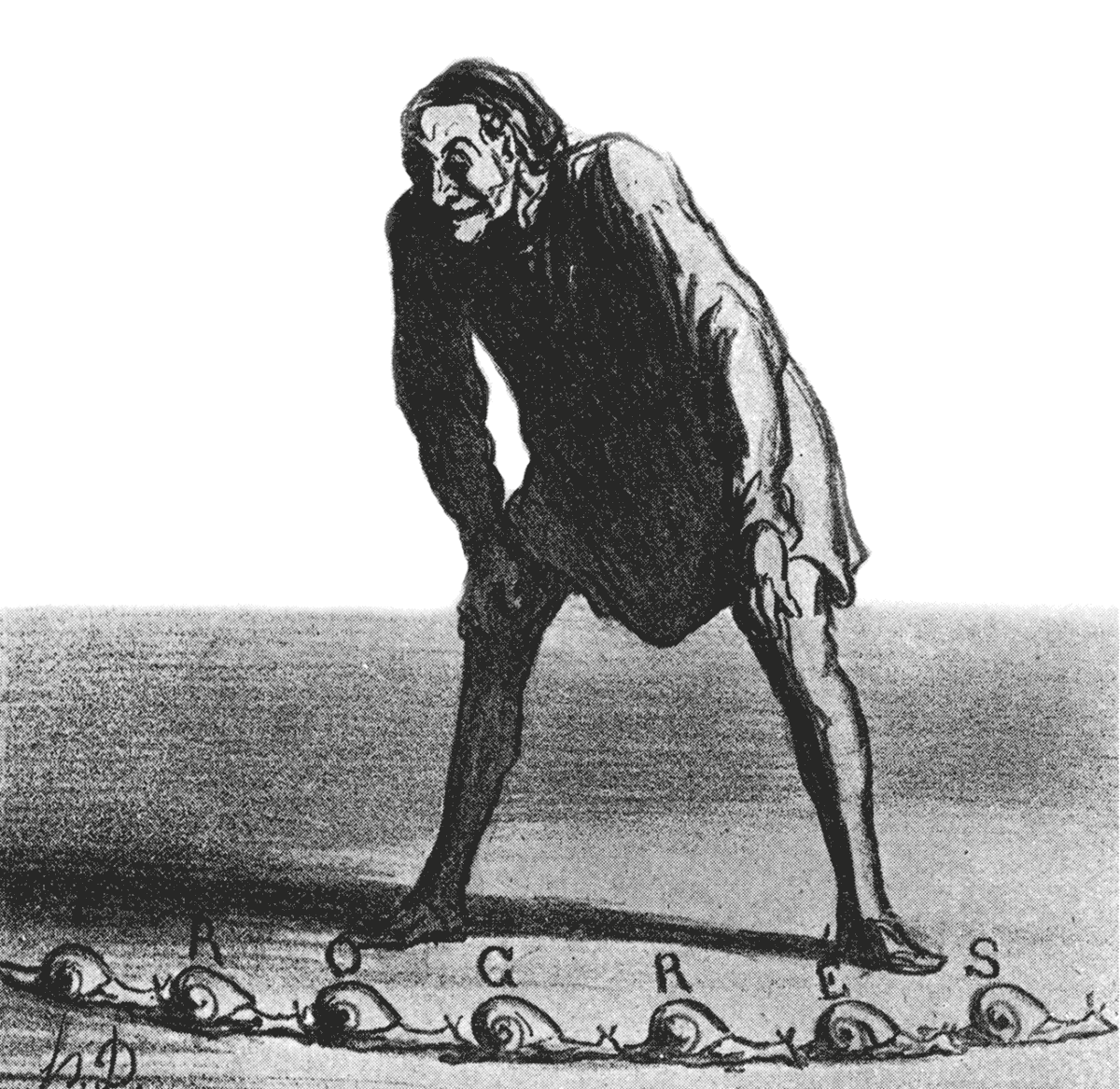

The book is worth the read for these colorful examples alone. Smith shares example after example of realized and imagined technologies. There's Honores Daumier's attempts to use snails as a form of encryption and telecommunication. There's Leibniz's reckoning engine, which predates Siri by centuries. There's Joseph Marie Jacquard’s automated loom in the 1800s, which predates the earliest computers. And there's Roger Bacon’s Brazen Head, an early stab at externalized intelligence.

It was refreshing to see the freedom of imagination of these imposing figures. Scientists were wizards, engineers were alchemists. There used to be an interplay of spiritual and material essences that is gone today. People assumed that underneath the brass and pneumatic forces powering Bacon's talking head were demonic forces.

Why shouldn't we say the same thing today when we fail to explain our LLMs? Who’s to say that demons don’t live in the edges between nodes in a neural network? When we say “all models are wrong,” might we not also say — “because they bear the mark of the devil, the father of lies?”

Perhaps the internet is made of demons! Who’s to say!

Anywho, chapter one does warn of some new twists the Internet introduces today. They're worth repeating here.

There is “a new sort of exploitation, in which human beings are not only exploited in the user of their labor for extraction of natural resources; rather, their lives are themselves the resource, and they are exploited in its extraction.”

The attention economy "threatens our ability to use our mental faculty of attention in a way that is conducive to human thriving.”

Never before has so much of our lives been condensed "into a single device, the passage of nearly all that we do through a single technological portal."

And lastly, that "human beings are increasingly perceived and understood as sets of data points; and eventually it is inevitable that this perception … becomes the self-perception of human subjects, so that those individuals will thrive most, or believe themselves to thrive most, in this new system who are able convincingly to present themselves not as subjects at all, but as attention-grabbing sets of data points.”

These won’t surprise you. If you want to resist the dehumanizing aspects of the internet, though, these four wedges are a good starting point: limit consumption, reclaim attention, put down the phone, don’t be your data, and so on.

This tendency of the internet to make you think of yourself as an extension of it, rather than it as an extension of you, is where the internet breaks from world-building tools of the past, including books and oral traditions. Still, all of these are "technologies that aid the human mind in exercising its innate, evolved capacity to get outside of itself (another term for which is ’ecstasy’)”. And so we should not neglect its promise of elevating ourselves as well.

This is my hopeful takeaway: that there are ways we can create a relationship with the internet that augments our collective world, i.e. our shared overarching reality, rather than breaking each of us into solipsistic ones. Smith points to Wikipedia is the rare example of an accomplished feat that remains uncorrupted. The challenge the internet presents to us as individuals is not of adapting to the new worlds we have created, but of staying grounded in the one that’s always been out there for us.