On Sight and Insight

Why would one hundred eyes see better than two?

Argus Panoptes was an all-seeing giant, the perfect sentry. With a hundred eyes, he could see danger anywhere around him. When one eye rested, others were alert. Yet Argus, assigned the simple task of watching a heifer, was lulled to sleep and slain by his enemy disguised as a shepherd.

Argus saw the shepherd, but he did not see the shepherd. He was awake but inattentive, awash in optical signal. Hera, Argus’ master, took his many eyes and placed them on the peacock, where they remain today, beautiful but blind.

The story of Argus shows that sight alone is not sufficient for a deeper kind of seeing — insight. To see not just the picture, but the meaning inside it. The eyes set the boundaries of the world, but within that world, we must choose what to focus on.

Argus had the eyes. What he lacked was attention.

It’s the same thing we all lack, most of the time. Moments of presence are the exception, not the rule, and they are a joy to experience. For me, these come most often in small moments while parenting.

Here’s how it goes:

I ask my child to do a simple task. The child fails. Surprised, I pause and look at the task again, in its fullness. I realize: how could this child do such a thing? How could anyone do this?

For example: time. A three year old cannot cannot understand hours, days, and weeks. For him, life is a stream of activities that just tapers out in his memory. What is time, when you simply didn’t exist a few years ago? Time is a partner to activities: bath time, reading time, story time, nap time.

I had forgotten how to see time in this way. To recover it, I didn’t need a sophisticated analysis, I simply had to look, differently.

To look inside of the thing I was so used to seeing. Insight.

Using a spoon. Putting a shirt on. Throwing up somewhere other than the carpet. Each of these simple tasks masks a deeper picture of social expectations and primate gymnastics.

But the big one is reading. Everybody reads, and everybody has forgotten how to read.

Books and specialists will focus on specific knowledge required for reading: the phonemes, graphemes, syntax, grammar, and the like. And it’s true that reading is full of this special knowledge, a ladder we climb and then discard once our eyes are trained.

I knew all these things when I started teaching my oldest to read, but quickly realized that this knowledge is not the foundation of reading.

Reading is, first and foremost, a struggle to control the eyes.

To read, a child must focus their entire mind on a pinprick, blocking out all distracting visual delights. Words are not large. Letters are not meaningful. To a child, they are scrawls, in a vast world.

And that is just the start. After locking their eyes, they hold it and process, search their existence for any possible meaning to attach, and then spit out a guess. While they do this, they must also silence every fiber of their being that screams, “LOOK AT THE CAT HOLDING A FISH ON AN UMBRELLA.”

Successful or not, they must move on, the next word. Two millimeters over. A ballistic saccade — left, right, up, down? — and they do it again. Again. Again. Again. Five letters, five searches, five eye movements, all of it taking time and attention.

This is what insight looks like: precise sensory machinery and unwavering focus.

And it’s no surprise that we, as primates, would associate insight — a mark of intelligence — with the eyes. Most of what we know about the brain we know because of the eyes.

Scientists demonstrated neural plasticity by manipulating the eyes and visual environment of kittens. Scientists probed the mechanisms of attentional processes by training macaques to play visual games in exchange for orange juice. Scientists mapped the human visual cortex using the eyes of undergraduate volunteers.

Studies on the eyes expose two things.

First, it shows off how wonderfully designed humans are to see. As primates, sight is our birthright. Our brains devote disproportionate real estate to visual processing. Our skulls evolved to direct our eyes forward, towards the oncoming world. Our retinas are honed to balance precision and accuracy. The mind starts at the eyes.

Second, it shows how monstrously violent a thing it is to command someone’s sight. Which, of course, is what is required to conduct any of these studies.

To map what is shown to an animal to what is detected by its brain to what is perceived by its consciousness requires precise control over three dimensional space, and the subject’s position in it. The subject must be affixed to a tightly controlled pseudo reality, a static visual arena, a palace of only sight and attention.

To limit sight and direct attention is to own someone else’s world.

The scientist starting her experiment: look at this.

The parent teaching reading: look at this.

The mobile app nudging users: look at this.

But what else does a leader do, other than framing reality and encouraging others to focus on a limited set of goals?

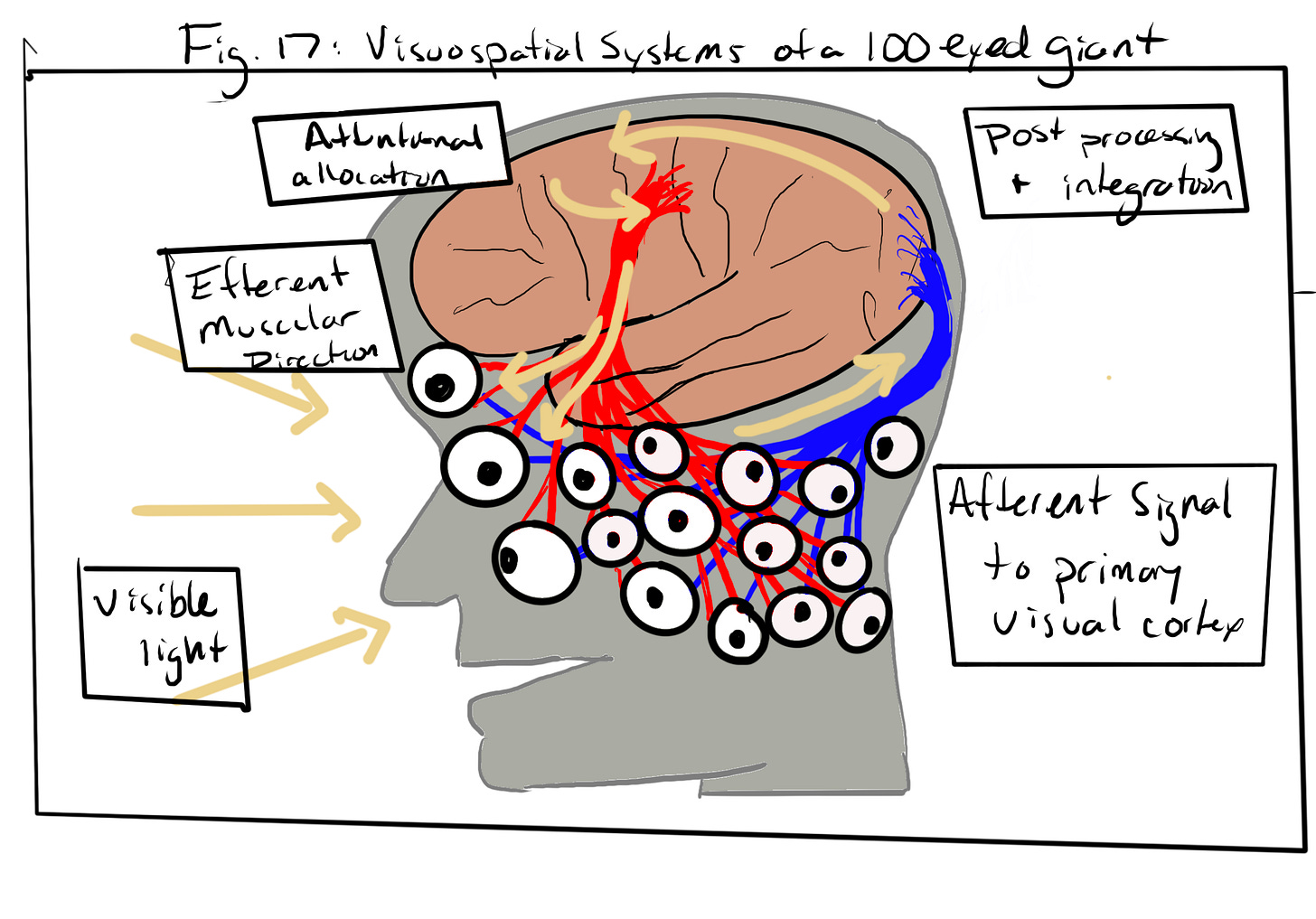

The question, then, is how does one prevent the gaze of an organization — the disunited giant with not one hundred eyes but one thousand or more — from becoming listless and glancing past the mortal threats staring directly at them?

If the organization cannot see, it needs better eyes. It needs to sharpen the mechanical processes that collect and make basic sense of its environment. It needs its sensory input to be fast, comprehensive, and reliable.

If the organization cannot pay attention, it needs executive function: top-down processes that select for salient stimuli, while suppressing irrelevant ones. It must discriminate between what matters and what doesn’t. It needs better focus.

What makes the data vendor obsession with insight so awkward is that insight cannot be outsourced. In no case will more data and prettier pictures and advanced equipment — more eyeballs — be sufficient.

Insight must emerge from within the organization. The systems have to work together; attention and the eyes are entangled. The eyes constrain attention, attention directs the eyes.

This system, working in service of life, is the only path to insight. Disconnected from this, the eyes may as well be on the peacock.

This is a really beautiful piece!

I love the overlap of Data Content and Dad Content. It just connects so viscerally 😄