Organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations. — Conway’s Law

Data professionals wage an eternal war against their systems becoming a decapitated mess of half-truths and suspect data products. But could it be that the “truth” is hard to align on, not because of the data, but because of the people?

“No! Flawless metrics will be trusted on their merits!”, we protest.

“Meaningful data will catalyze meaningful decisions!”, we shout.

“All will bow to the single source of truth!” we — wait, who said that?

But Conway’s Law is simple: the system cannot escape the constraints of the organization. If the data system is not a key channel in the communication structure, it will never quality test, story-tell, or cloud-scale itself into human relevance.

So, if we as data professionals want to establish systems that generate truths, then we must ask: What are the existing communication structures in my organization? How does the organization generate a view of the world that drives collective action?

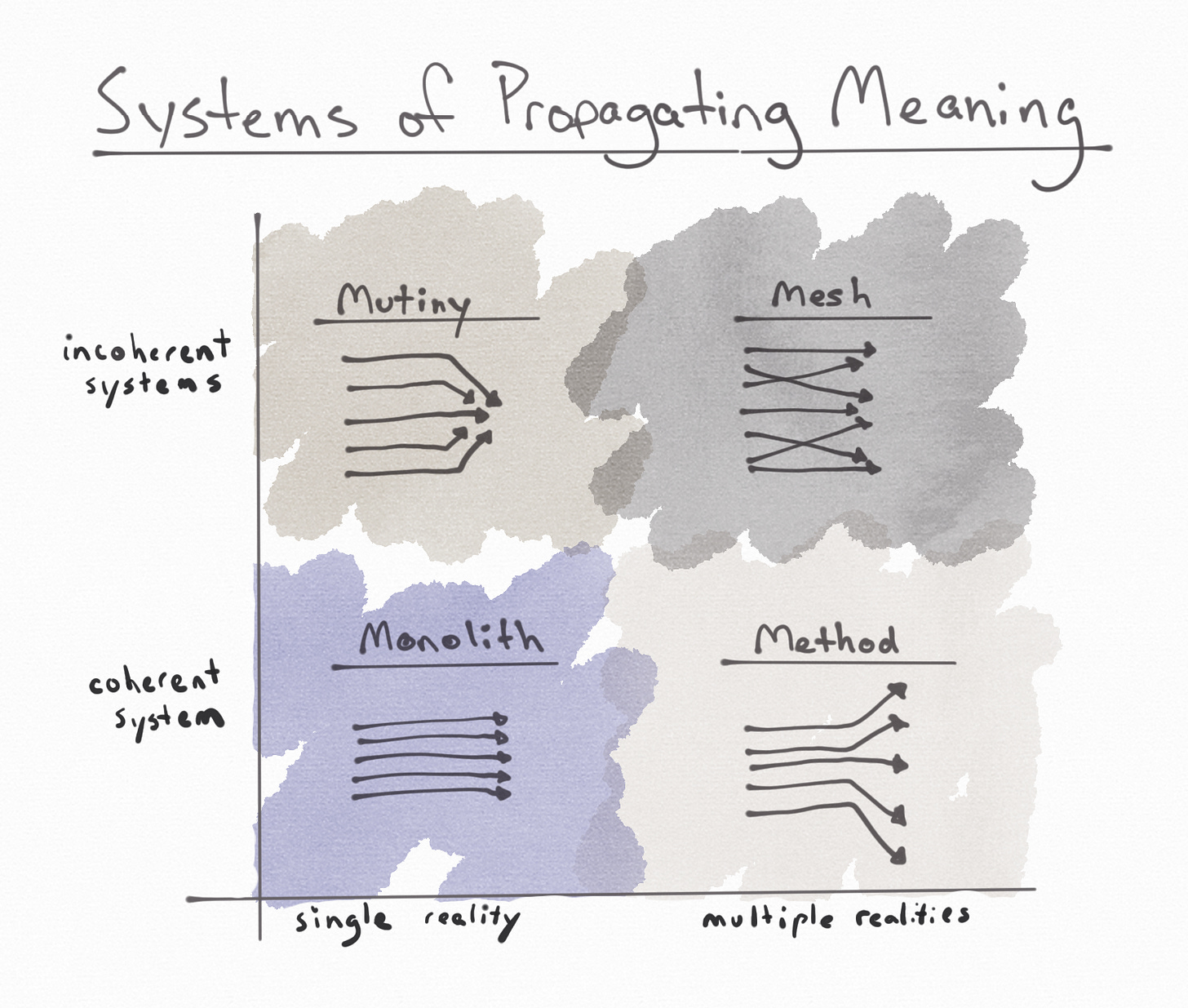

In other words, what is the Truth Architecture of the organization? A truth architecture is one or more “communication structures” that generate a worldview that people align with. These architectures vary along two dimensions:

the number and coherence of communication structures that generate trusted information

the number of inconsistent realities tolerated by the organization

Combining these dimensions, we get a magic quadrant of possible truth architectures: the monolith, the mutiny, the method, and the mesh. Let’s take a quick spin through history for an example of each, before returning to the plight of modern data professionals.

The Monolith

The Roman Legion is not a consensus-driven organization.

It is regimented, disciplined, single-minded. When the legate orders a march, the legion marches. When the legate commands an attack, the legion attacks. Failure to follow orders could lead to decimation — death by clubbing for 1 in every 10 soldiers in the unit.

The legion was innovation par excellence in classical military tactics. The cohesion of thousands of individuals into a single deadly combat unit brought the Romans victories, territories, and lasting wealth. It opened up deadly new tactics, like the “turtle shell” formation: a line of infantry multiple men deep that could rotate turns on the front line so that enemies always faced a fresh opponent, even hours into battle.

The immense pressure of constant life-or-death situations creates an epistemic turtle shell of its own. Curiosity, questions, opinions: these are not the sorts of contributions that curry favors in the legion. Courage to adhere to the plan, bravery in execution, a sense of triumph of their shared reality — might is right! — this is the only truth known to the legion.

While commands may flow down from superiors, the entire organization is committed to preserving the unit: all for one and one for all — or death. To function, the legion and its leadership must build a powerful monolith primed for battle, both physically and intellectually.

The Mutiny

In 1274, Saint Thomas Aquinas (PhD) passed away. He left behind his Summa Theologica — the Summary of Theology — which answered all the important questions a human could ask about God, Creation, and Man’s Purpose.

If you were a part of the Catholic Church back then — and you were — you could go ahead and close the book on the subject, thank you very much.

In 1517, Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses. Luther reopened the book.

What followed was the Protestant Reformation, a bloody splintering of the church into faction after faction after faction. A key catalyst was Luther’s powerfully subversive doctrine of sola fide: “We are saved by faith alone”. Read another way: “We are not saved by the Catholic Church.”

The Catholic monolith was a one-stop-shop for truth. There is one reality: God’s reality. There is one way to understand that reality: through the Church. Questions about suffering? Let me direct you to our priest, who will check with God on the matter. Need absolution from your latest sinning spree? Drop a check in back and we’ll settle it with the big man.

Luther “democratized access” to God by setting up a direct line from the individual to eternal salvation. The 95 Theses did not dispute God’s existence. Instead, they took a single coherent system that controlled access to knowledge about God, and shattered it.

This opened the door to competing systems of understanding God, of organizing churches, of sanctifying (and condemning) behavior. It fomented religious wars, state-backed churches, and some way-too-intense arguments over baptismal practices. But it also threw off a stifling truth architecture and opened paths to new ways of knowing the world.

The Protestant Reformation was an epistemic mutiny. Everyone agreed on the existence of a single, ultimate reality. But no one agreed on how to establish it.

The Mesh

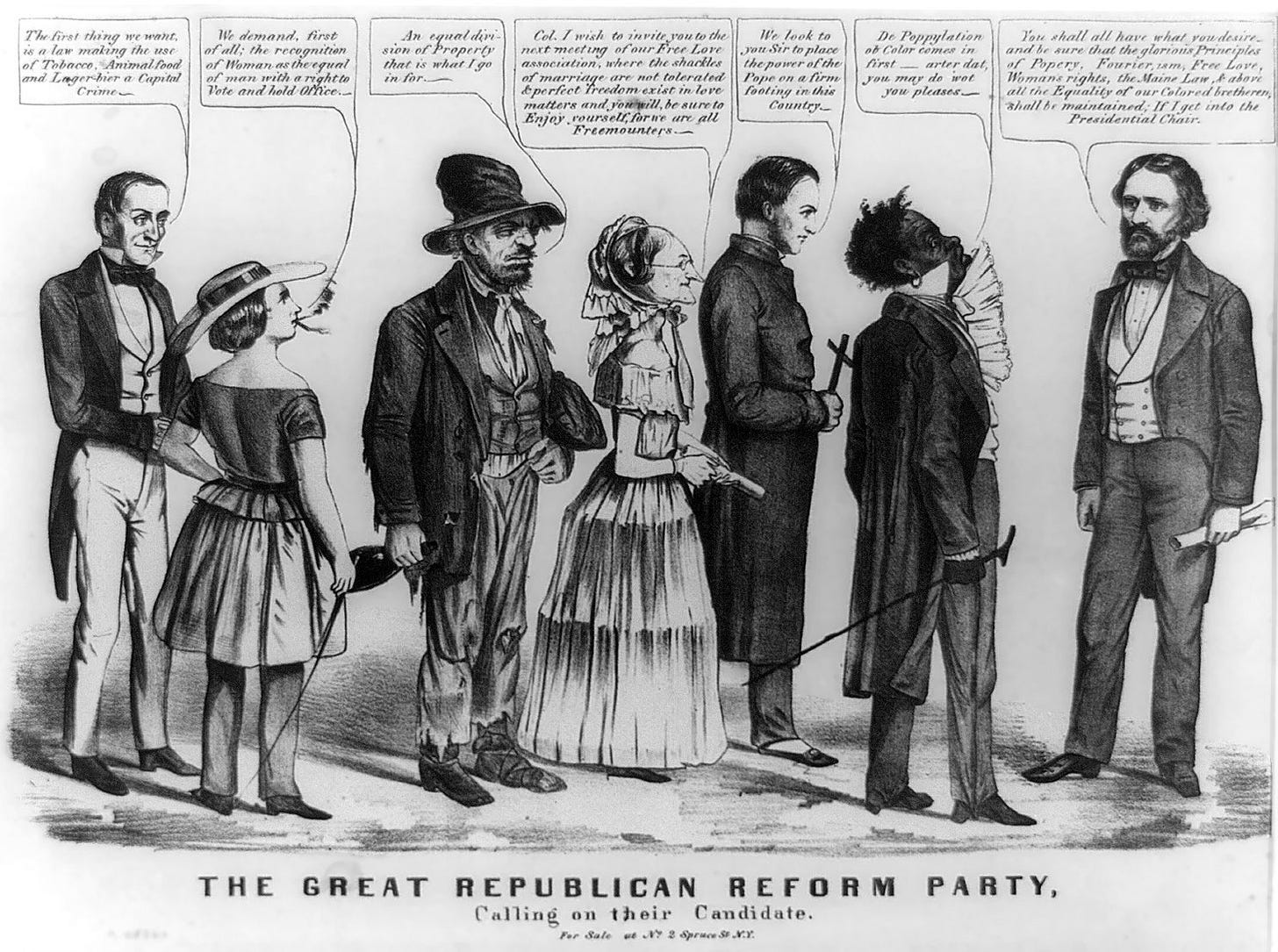

The Republican Party is ascendant.

It is 1860 and is only 4 years since its founding. Abraham Lincoln has just been elected president. It is a striking success for a nascent coalition built from of myriad smaller groups, including groups supportive of feminism, alcohol controls, major infrastructure projects, and most importantly, emancipation. Started in a Michigan schoolhouse, the party received almost no support from Southern states.

What happens next is, of course, the Civil War. But the lesson for us is in how an organization transitioned from non-existence to instigator of the War of Northern Agression to fighting to preserve memorials of Southern icons.

One part of the answer is that there is only a loose coupling between the motivations and reasons for supporting the party, and the actual actions made by the party.

The political party does not use systems that generate answers about reality, it has mechanisms to provide responses to external forces. Sweeping claims and fundamental truths that are declared today may be modified tomorrow, depending on the flow of events. If religion is high mathematical theory, democratic politics is industry data science. (“Just use logarithmic regression!”)

Like a Katamari, the primary objective of the political party is to mobilize as many individuals as possible into a voting force. The result is an epistemic mesh that continually globs new ideas and rationales into its coalition, even as others peel away. This flexibility gives it an impressive sticking power, even as the world changes around it, at the cost of conformity and coherence.

The Method

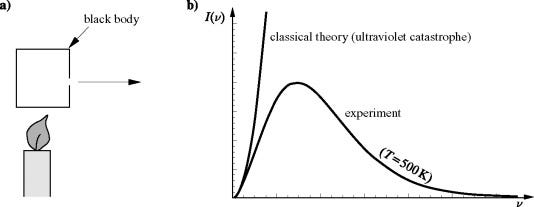

It was a catastrophe, an ultraviolet catastrophe.

Lord Rayleigh and J. H. Jeans had developed an equation to describe how “black body” materials should absorb and re-emit radiation. Everyone agreed it was a great equation, a real banger of an equation. It respected all the known laws of physics and it worked great in experiments — well, most experiments.

You see, there was an annoying little problem. At high frequencies of light (i.e. ultraviolet light), Rayleigh-Jeans Law did not square up to measured reality. And when this was replicated again and again, it began to open up the possibility that the dominant reality of Newtonian physics was not the only one possible.

The ultraviolet catastrophe presaged a paradigm shift in the modern scientific community. And while quantum mechanics has had revolutionary consequences, it never precipitated the same sort of cultural upheaval that previous scientific revolutions precipitated, especially among scientific professionals.

This intellectual resilience stems from a shared epistemology grounded in the scientific process. Under the scientific method, all propositions are worthy of consideration, as long as they submit to the process. Any subject may be placed under the microscope, so to speak, and any outcome is tolerable based on its merits.

The truth architecture of the scientific community is methodical. That doesn’t mean it is harmonious, immune to failure, or self-evident. In fact, much of the work of senior scientists is not in designing clever experiments, it’s extracting themes and reconciling divergent results, and building the paradigm within which the community operates. But the work is done with the humility of knowing we can only ever have an imperfect picture of reality.

The data professional always operates within a semantic milieu, a truth architecture. The monolithic startup driven by a charismatic CEO. The meshy enterprise and its tangled mess of systems. The methodical R&D group with its tinkering innovators. The mutinous midsize company and its C-Suite fights over whose department initiatives are really driving growth.

Global companies naturally move towards growth: more people, more systems, more conflicting worldviews. To facilitate action, communication systems will be established. But how this happens is not set in stone.

One path is that of Power. A commanding officer rallies his troops behind a powerful narrative — we are winners — and charges the company forward into battle. They fight and win, and as they win, they grow. Lieutenants are promoted and write their own histories. When internal conflicts arise, a winner is determined and the loser is dismissed. The company grows, accrues territory, builds infrastructure, but ultimately represents a loose federation of organizations, autocratically managed.

The other path is that of Consensus. The leader starts with a question: What do we do next? She invites others in, seeks opinions and evidence. As success is found, decisions are pushed down: follow the process, ask the questions, look for answers. The reach of the company increases, but instead of breaking apart into factions, groups maintain lines of communication. As the company grows, it retains a posture of learning, not conquest, and assimilates new talent efficiently.

Data professionals can build consensus as the company becomes more diverse. Data systems can establish methods for understanding the world even as it becomes more complex. Data literacy can create pathways for anyone to contribute equally to the organization’s Truth Architecture.

So before you go about setting up your Single Source of Truth, ask yourself: is there even a single truth out there to be sourced?