The Optimetricist

Is the glass half water or half value?

This is part one of a three-part series exploring attitudes towards data.

Thirteen weeks ago, Jamil Khatun sat down at his usual table for his usual lunch when he noticed something unusual — an ornate glass cup partly filled with water. It rested on a white “X” made of masking tape.

Was it a forgotten heirloom? A temporary leak fix? A coded message?

Each afternoon, Jamil studied the cup. It didn’t budge, but it changed: the water levels fluctuated, some days higher, some days lower. Inexplicable. Fascinating.

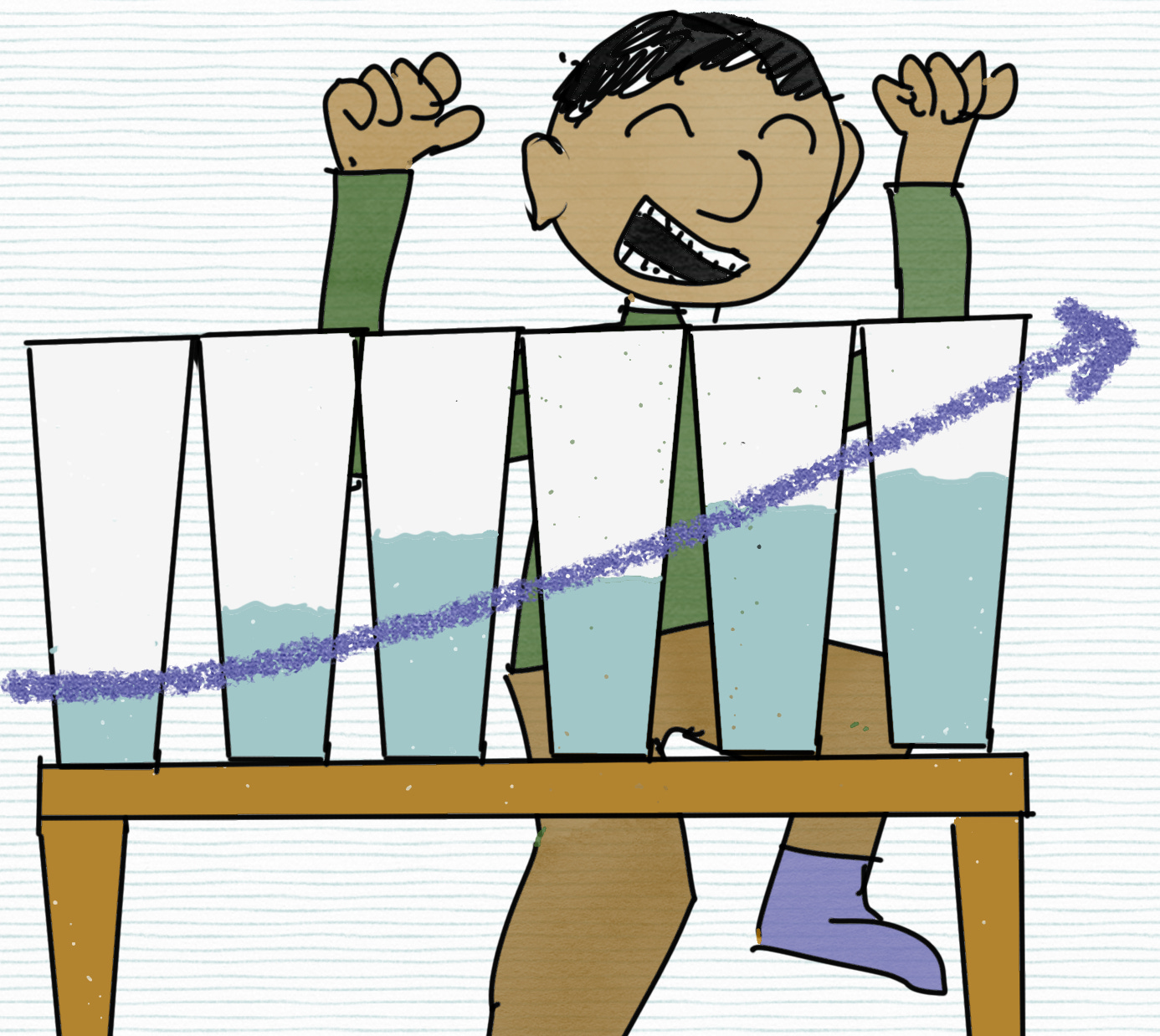

Jamil became a steward of the cup. He measured the water level each day. He tabulated the measurements. He built bar charts, then derived secondary metrics — rates of change, relative fullness. He checked for correlations and cycles — weekdays, seasons, weather patterns. He gave the cup a history.

Jamil became an emissary of the cup. At first, colleagues mocked him. “Cup full yet, Jamil?” they asked, feigning curiosity. Jamil handed them the weekly report, an inkjet-printed flyer with clip art and commentary. He replied, “Not yet, but we’ve seen a full recovery from the ‘big dip’ a few weeks back that caught everyone by surprise!”

His tenacity converts skeptics into fans. The cup’s metrics became familiar, its history storied, its knowledge common. Lore crops up independently — “I hear it was put there by the government… I hear Jamil comes in at night to fill it up…” Closet quants suggest new metrics to track, such as pH levels, temperature, and salinity. Interns hack into Jamil’s Google Sheet, pilfer the data, and build a silly but captivating app. A sales manager starts a betting pool to estimate when the cup will reach maximum capacity. The office receptionist buys party favors for the inevitable Full Cup day.

The cup is a cup. The numbers are numbers. But suddenly, there is more. A micro-society blossoms. It has routines, lore, standards — a language. The cup is transubstantiated: a vessel of spirit rather than water.

Soon, Jamil expects, the cup will runneth over, bets will settle, festivities will flare. An artificial, ephemeral reality meeting its inescapable end.

Or perhaps — this is only the beginning? Jamil sees the demand, the delight, the data, and he thinks — if this is the value one cup can make in the world, what could he do with two?

Like words, metrics are a simplification of reality. The only difference is that metrics are dynamic: changes to a metric value are supposed to reflect changes to the reality they describe. They are powerful proxies, but proxies nonetheless.

A stock price flattens the reality of a sprawling global enterprise. A gas price masks a complex supply chain with geopolitical consequences. Weather predictions flatten dynamic weather systems down to emoji-compatible pseudo realities.

But we can also go the other way: to create a more complex reality from something simple, mundane, or ridiculous. Our pal Jamil took something intrinsically meaningless and transformed it. Such is the power of metrics.

People who want numbers to mean something are optimetricists. Like the optimist who puts a hopeful and positive spin on every situation, the optimetricist has never encountered a number they can’t explain.

The most extreme optimetricist believes that this data, this number in front of them right now, represents the best numeric representation of the world, across all possible numeric representations of the world.

If a new chart comes across the desk, they jump to interpretation — “Oh, of course, DAU is up, we just released that new ad campaign” — or they argue with its implementation, perhaps — “We aren’t surveying the right people” — but the optimetricist relies on the validity of the metrics themselves.

The optimetricist trusts that numbers mean something. In most cases, they do.

But they don’t have to. Because metrics are stand-ins for the world, they can be tightly connected (e.g. temperatures) or loosely connected. Consider bitcoin prices, and its fluctuation the past few years. Has the technology changed? Not significantly. It’s the world on top of the technology, the social reality, that has changed.

I won’t argue that any reality is more “real” than another. Plenty of people have real cash (or real cash losses) from the crypto craze. My argument is that if you could choose to believe that crypto prices are “overvalued” or “undervalued”, you are choosing to live in a world where “crypto value” is a meaningful concept worth organizing human activity around. You are optimetricistic about crypto value.

The optimetricist can look like a fool. Even if some models are useful, they are all wrong. So what should we call someone who puts faith in a model? At a minimum, they are wrong. In the worst case, they are wrong and useless.

But sometimes being simple and foolish is the best way to get a whole bunch of people rallied around a common goal, to stay in line, to create something new. Sometimes, the most effective leader is the one who can boil a dynamic and complex whole into a few simple and persistent parts.

This is the power of metrics wielded skillfully: to create useful new worlds for teams to inhabit and organize within. Whether or not they are a bit silly when compared to reality is beside the point.

Feeling a bit like Jamil as I’m currently tracking the office temperature and sharing results with the team...

Great post, Stephen - looking forward to reading part 2 and 3. Or am I being an optimetricist in my anticipation of a 3/3 📈?