Elitism as the Mid-Career Growth Engine

Technical excellence begins in wonder but is honed by disgust

There are only two types of journal clubs.

The first is managed by graduate students. The leader picks a recent Nature paper, no one reads it, and for thirty (thousand million) minutes everyone avoids eye contact and pretends they aren’t just making comments that are paraphrased figure captions. Everyone is embarrassed that they aren’t “smart enough” and should have prepared more. The air reeks of guilt.

The second type of journal club is led by a postdoc. Its parallel is Fight Club. The journal article is still a Nature paper, and still, no one has read it. But the postdoc — who didn’t get any GODDAMNED sleep last night because of that GODFORSAKEN reviewer two, not to mention his GODBLESSED teething infant — comes out swinging: “This paper is a piece of shit. This whole field is going to hell.”

Gauntlet thrown, the postdoc must now rationalize why this paper is, in fact, terrible. Again: no one in the room read more than the abstract. But now, with the polarity of the discussion established, the room works together towards the apocalyptic thesis.

An N of 500?! That sucks — right?

A two-sided t-test? What are they thinking?

Check out this nonparametric crap they’re trying to pull!

Gradually, the room evaluates article specifics. Gradually, they understand the reasoning. Gradually, they decide that, while the paper is garbage, no question about it, maybe the authors had one or two good ideas we could look into. And we should definitely check out the code they published, just to make sure, you know, it works.

The active and violent spirit of the postdoc is a critical difference in the ways that early- and mid-career professionals grow in their craft.

(Late career professionals have no need for journal clubs. They already read the grant or budget and know the outcomes.)

It takes animus to push conversations out from the boring straits of explanation and pedantry and into the frothy, conflicting waves of exploration and world expansion. It takes a bit of pirate swagger. It takes a separation of the world into mateys and landlubbers.

In other words, to grow in the mid-career, you must become an elitist.

I don’t want to go into the political ideals here, of aristocracies versus democracies, etc., etc. I am talking here about a sense of elitism as applied to a specific craft. Sports and art both exhibit the obvious skill asymmetry I am thinking about here.

The tenets of this technical elitism are:

You believe there are higher and lower tiers to the practice of your craft, and

You aspire to be — or at least admire others being — in the higher tier.

I take it for granted that this sort of elitism is natural and proper. To not believe that you could be better at anything, and want to do so, seems dysfunctional.

But elitism only becomes useful at a particular stage of development. Earning the white belt is almost purely knowledge and a bit of practice. Getting to the black belt requires not just skills, but a mindset: determination, resolution, and yes, snobbiness. You must believe that having a black belt is worth the effort and that having a black belt is better than not having one.

Elitism manifests in the body as disgust: a visceral aversion to lower-order practices. Disgust is the precursor to good taste. Disgust is a powerful, pre-rational behavioral guide. It repels you from unhealthy, rancid things, and motivates you to seek out healthier experiences.

As a psychological mechanism, disgust works the same whether we’re talking about wine, cheese, fine art, or software development. Consider the Zen of Python:

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

A beginner reads this and focuses on the left side: beautiful, explicit, simple. They think, “That sounds wonderful!”

A veteran reads this and feels the right side: ugly, implicit complex. They think, “I know this pain.”

I imagine the author bent at his desk, wincing as he flits through internal project retros. The abject disgust of reading Charlie Smith’s code. The disorienting miasma of the WoopeeWidget microservice. The leaning tower of KoolAppCo’s main backend services. Only with sublime concentration can he bend his mind toward his ideals.

Pain, agony, disgust — I admit all of this is a bit dramatic, even for me. But for those who write software seriously — as for those who design architecture, literature, or any other art form — the craft is a creative expression.

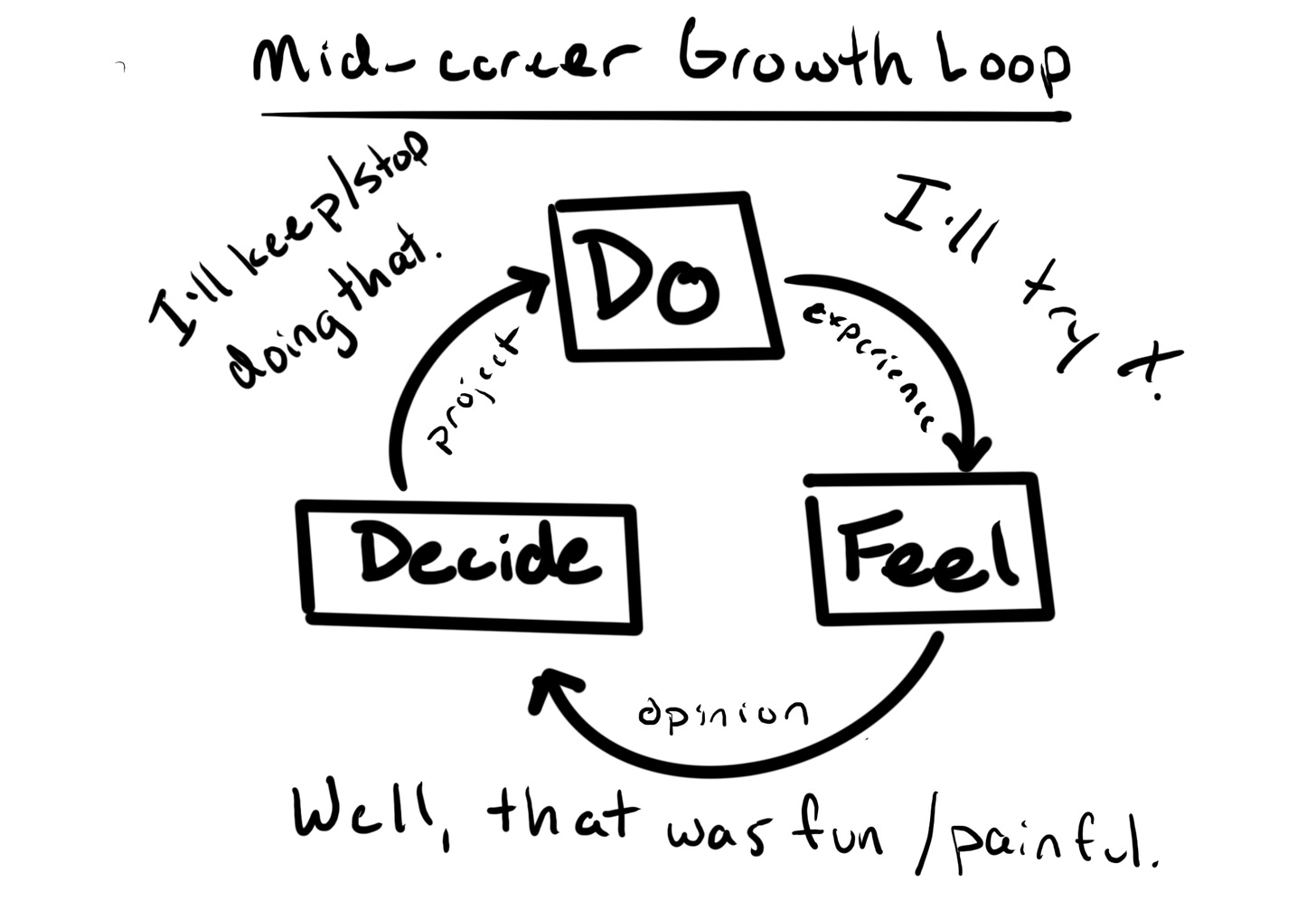

The power unleashed by adopting an opinionated mindset is energetic and stylistic. Like the writer who learns only syntax and grammar, but never adopts a voice, the mid-career developer can get stuck in a technical meatgrinder. They’ll burn out or bore out because they never injected their identity into the growth loop.

After the beginner’s scaffolding of skills, what matters is the mechanism for deciding what’s next. That’s where opinion and aversion — not reason! — comes in.

The mid-career professional is at mile fourteen of the marathon, past the runner’s high, past the crowds and pomp. She has to keep moving, focused on the next step, and the next, on her tempo, and her goals. When you are elitist, small decisions add up to minutes, and minutes matter.

What matters in the middle of the race is not the outcome, but the attitude about the outcome. It’s appropriate to recognize limitations and update expectations accordingly. It is not being the best that matters, but continually striving towards the best, and refining your definition of the best.

So whether you’ve read the Nature paper or not, take a stance on it. You might find yourself in the wrong, but I’ll bet you learn more and have more fun. And rest easy — you’ll never be more wrong than the people who use R for data engineering. Goddamn maniacs.

The part where you write about disgust being the precursor to good taste is particularly interesting to me. I need to think about that.

Enjoyable read. Should a distinction be made between being an expert and being an elitist? To be an elitist is to have opinions for the sake of being perceived as being better or more refined than others; how one is perceived is critical. While the true expert hold positions based on their correctness, regardless of how it influences their status.