The primary requirement for a world is that it’s inhabitable. The “real world,” for example, is a great place to spend your time, but plenty of people live elsewhere.

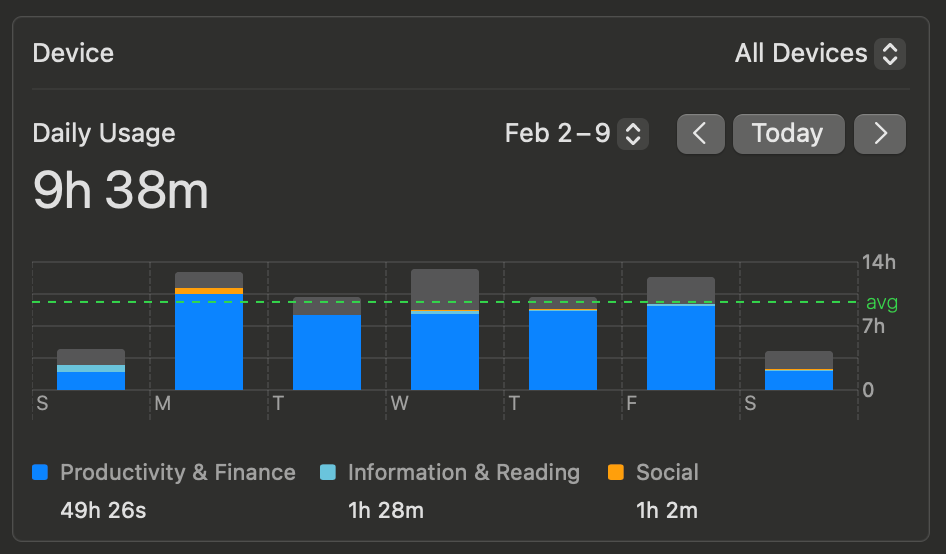

Case in point: the below report of a week’s worth of screen time. According to my screens, I spent nearly 10 hours a day engaged in “productivity and finance.” If my house provided the same report, I’d see a near-perfect correlation with my basement office. Shouldn’t every bit of evolutionary design work against this situation? How can an adult human stand to sit in one room, for hours on end, burning his retinas, slouching into senility?

Job World, obviously. The most self-aware part of me is not in that underground prison at all. When I turn on the space gray lightbox, I’m whisked off into another world, one where I barely even have a body, one where I can single-mindedly engage in my own unique brand of “productivity and finance”.

This human ability to inhabit virtual spaces in addition to physical ones is central to the idea of worldedness. Remote Job World is robust: I can spend 50 hours a week in it, week after week. It pulls me in. Family World pulls me out. Eventually, Human Body World wins the battle and gets me to sleep.

I don’t want to wade too deeply into the philosophical questions. I am not concerned here with ant colonies, LLM consciousness, or the nature of reality. Venkatesh Rao, as usual, has published great work on this subject already. In This is the new real world, he writes:

Accounting for consciously shared worlds like religions, fandoms, and nationalisms, as well as commonalities that arise from obvious and lazy lines of thought or imitation, there are perhaps a few thousand to tens of thousands of non-trivial distinct inhabited worlds out there. Of these, perhaps a few hundred are significant enough to require accounting for in any analysis. The rest are, at best, butterflies flapping in the chaotic weather-systems of history, hoping to cause hurricanes.

Many of these butterfly worlds, though, are consequential on a local or personal scale. I know from experience with my own FamilyWorld[#391842], for example, that boundaries, rituals, and intentionality over time add up to create a deep sense of purpose. Startups are small worlds with big ambitions; enterprises are mid-size worlds that face the daunting challenge of sustaining themselves at scale. A world doesn’t have to be universal to be worth minding.

There is, however, a common structure that needs to be in place for them to be effective. My goal in this piece is to lay out a framework of thinking about the elements of a world—what makes it strong or weak—such that we might begin to analyze and tinker with the worlds we experience in practice.

Strong worlds provide structure and meaning.

In his book A Non-Anxious Presence, Christian author Mark Sayers paints a narrative of the ancient world as a series of tribal clashes. Through victory and cultural assimilation, successful tribes grew into large civilizations and developed self-perpetuating cultures—Egypt world, Babylon world, and so forth.

For the adherent, the chief purpose of culture is to absorb anxiety. (The blunt version is, “Join us, and we will protect you.”) Framed positively, strong cultures provide a strong sense of belonging. By participating in that world, the person can align themselves with society, understand what is expected of them, what their routine would be, where to get news, and who to admire or jeer. The culture provides, if not the good life itself, its recipe for the good life. A script.

The strongest worlds become major cultural and political forces. They vie against rivals for primacy. The Roman World’s imperial expansion brought massive amounts of physical territory under its influence through military and industrial prowess. Later, the Christian World won allegiances with its spiritual world through an alluring foreign message of love and resistance: “Be in the world, not of the world.” (This quickly turned into an unnatural merging of the two.)

In both cases, the worldbuilding process was as much a story of incredible logistics as it was of pivotal plot twists. Sayers identifies five characteristics that are shared by all strong worlds.

A defining narrative that builds a foundation of exceptionalism, i.e. why this stronghold is superior to rivals

A hierarchy, specifically, a hierarchy with clear leadership at the top

A way of life with values, protocols, practices, and patterns that align with the stronghold’s power

Communication channels to push the narrative and way of life, and to limit dissenting voices

Systems and institutions that formalize the stronghold’s way of life

There are two major points to make about this framework.

First, these are design decisions. Yes, for the world to function, humans need to participate—a “way of life” needs to be lived. In the abstract, though, a creatoir can design the world without humans, much like we might do with a piece of software. It’s the “game” aspect of an infinite game. The players are responsible for keeping things going, but they must operate under game roles, game scripts, game physics, and game rules. Designing the game and getting players to play it are separate, although they interact at scale.

On the other hand, humans have an incredible ability to steer, expand, fork, bork, port, or otherwise mutate the worlds they inhabit. A missionary, for example, leaves the Christian World to go plant a seed of it elsewhere. Despite physical isolation from the normal patterns of Christian civilization, they may maintain their way of life (prayers, feast days, study) with the goal of starting some new, hybrid world.

This virality means world structures can change quickly, even in the ancient world. Post-Internet, though, the worldscape has changed—for the weirder.

The Internet makes weak worlds strong.

One of Sayer’s main themes is a cultural oscillation between eras of clear cultural dominance (strongholds) and “gray zones” full of cultural uncertainty. (“Chaotic eras” and “stable eras” for my Cixin Liu fans.)

According to him, industrialization precipitated a chaotic era that stabilized in the late 1900s; with postmodernism and digitalization, the early 2000s have seen cultural chaos reach a fever pitch. Institutions are weak and weakening, and tribal worlds are overpowering the more coherent and inclusive strong worlds.

My take is that these digital-native tribal worlds is possible because the Internet solves two major problems in the worldbuilding process: systematization and communications.

Previous worldbuilding efforts were costly. Only the most powerful forces—family, geography, profession, political party, religion—were capable of the organization required to build strong worlds in which people could spend large parts of their lives. Creating institutions, shared ways of life, authoritative communication channels, and relevant narratives need investment and upkeep.

Now, all of those things are cheap. The phone and the Internet make worlds easy to build, maintain, and distribute—and costly for individuals to suppress. Worlds can systematically intrude into our lives with a buzz in the pocket.

In other words, we now live in a society with access to innumerable weak worlds: echo chambers, filter bubbles, walled gardens, digital enclaves, tribes, fandoms, communities, information silos, in addition to legacy strongholds.

These worlds are easy to leave and easy to enter. Compared to older strongholds, though, they are narratively anemic. No one is actively making the argument that anyone ought to spend a great part of their life in the “basic user” social rung of Netflix World, but in practice, it’s incredibly easy to do so. It’s been engineered to be so by ingenious constellation of technology. The ethical question doesn’t even get asked, much less answered. Veni, vidi, victus sum.

Platforms are worldbuilding tools.

So, for good or ill, the Internet is a worldbuilding workbench, with the major platforms as the toolkit.1 Take this publication, for instance, which is housed in a mysterious coastal rock formation on the nether ends of Data World.

Data World has a thin but distinct narrative (“so hot right now” mixed with “pervasive existential dread”); a role hierarchy (influencers, readers, practitioners); a pattern of activities (podcasts, reading O’Reilly books, trailing comma jokes); communication channels (LinkedIn, Bluesky, Substack); and systems (toolchains and problem spaces). The Internet makes all of these things easy to discover, create, enforce, and distribute. The fact that it’s not managed centrally makes it vulnerable to co-opting and hype cycles, but it doesn’t make a practical difference to those who spend their time there.

The platforms themselves don’t provide a world-defining narrative, except to support their own existential drive. The business model is to let creators do that. There is an overarching narrative, leaked by key metrics, which shows the hand, which is, “spending time on the app is a good thing.” We want more of that.

This is as much an opportunity as it is a challenge. We are deep into a marketplace of worlds. Few people now argue that these worlds aren’t “real”: they take up our time, they catalyze relationships, and they can burst through in unsettling physical ways.

For people who care, there are real, practical levers to making the best ones even better. The chief lesson from the platforms is that, in the Internet era, systems beat out stories over time.

Systems beat stories in the marketplace of worlds.

At the platform level, the B2C worlds—fandoms, entertainment, and the like—have narratives that mostly devolve into (1) show up, and (2) transact. The town square! Dive into anything! See what’s next! But this is not the right cut at the human level. It’s not “Substack” or “Productivity & Usage” that users inhabit, but the worlds emerging out of them.

It’s when worlds emerge across platforms that things begin to get interesting. In Moving Castles, Arthur Roenig Baer discusses a thoroughly techno-centric way of setting up these smaller worlds in a way that is immune to platform capture. Chief traits are that these worlds are collective, portable, modular, and interoperable. Creating worlds that support even one of these elements is hard work anywhere, much less on the public Internet.

But — there already exist many worlds that (1) span platforms, (2) meet all the requirements for worldedness, and (3) have dedicated, motivated inhabitants with financial backing. They are sturdy worlds, mediocre worlds, where many people spend much of their time, whether they want to or not.

The most interesting one, to me, is the corporation: a class of world that has long had to vie for loyalty, interoperability, and fitness in a busy and changing world. With the digital revolution, it has to deal with multiple layers of fracturing, not just across people, teams, and technology, but across history and geography. A shared Google Drive doesn’t cut it for coordinating across these internal worlds. It’s frustrating for inhabitants when a single world is experienced as a broken flotilla of systems and channels.

At the systems level, nearly all of this world coordination is mediated through data and data interfaces. If the interfaces are clean, the world takes on a sense of reality that is easy to lose yourself in. Systems and notifications cascade upward into a larger narrative and social structure. If they’re not, coordination breaks down, culture is stymied. “Productivity and finance” grounds to a halt.

Leaders will need more than stories and org charts to keep their businesses functional over the coming years. They’ll need to make sure their world, and the systems that comprise it, are strong.

The dystopian element is central here, but it’s handled better by others. I take for granted that the Internet of today is mostly a vehicle for psychological disease. At the same time, it isn’t going anywhere, and it presents new opportunities for healthy civilization. Better to build forward.