For generations, children have turned to Watty Piper’s The Little Engine That Could [Grosset & Dunlap, $8]1 to learn the power of positive self-talk: “I think I can, I think I can!”

A more careful read, though, reveals that the optimistic little engine is not the primary protagonist, whatever the title. The real hero is the one who asks, “Do you think you can?”

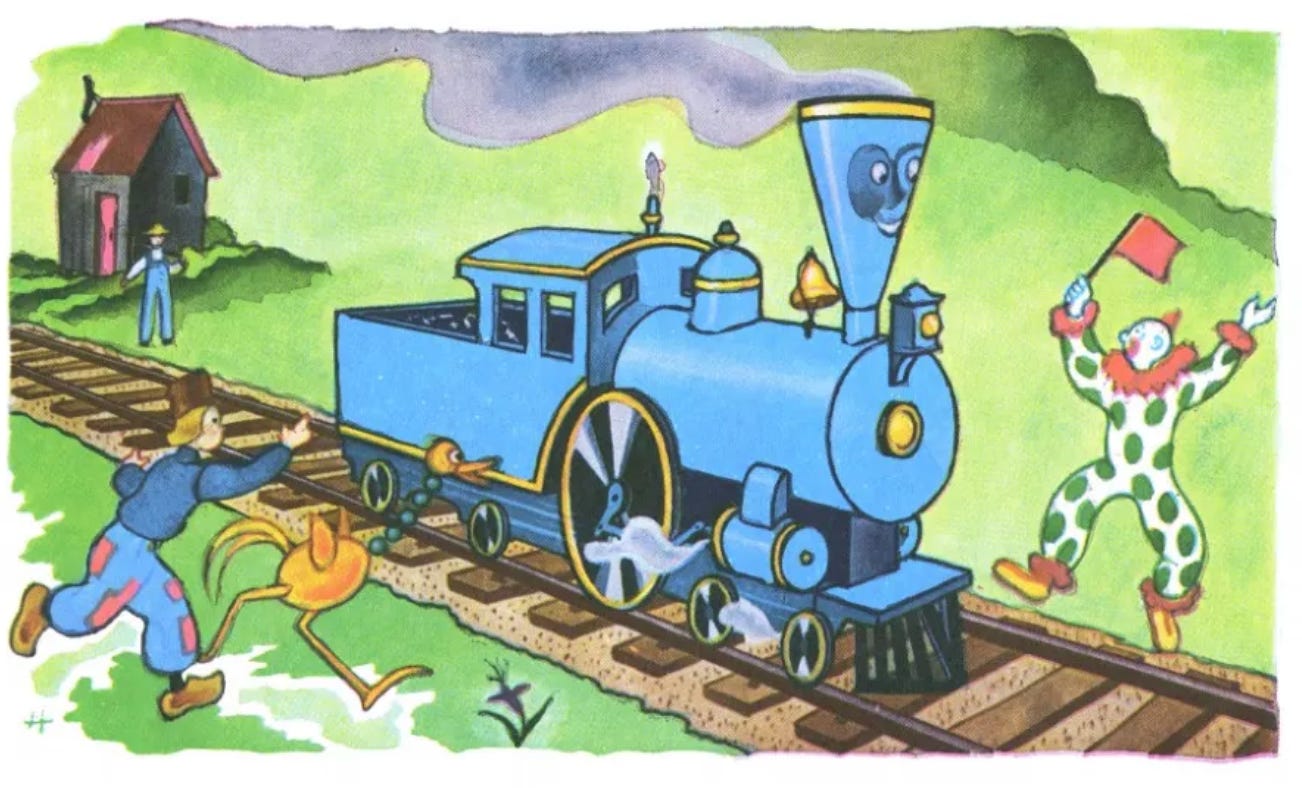

The Little Engine follows a shipment of fruits, candy, and toys over a mountain pass that gets stranded when its engine breaks down. Various capable engines pass by the broken-down load until finally, a little blue one stops and decides to carry it to its destination — despite being a little engine, despite being used only for “switching trains in the yard”. It’s a triumph of can-do spirit, with everyone ending up happy — the engine, the delivery service, and the consumers.

But it wouldn’t have happened without the pluck and persistence of the shipment’s project lead. This character is not a fancy engine, but a silly toy, the “funniest little clown you ever saw”. In the story, the clown goes to humiliating lengths to attract the technical assistance he needs when it becomes clear his project is off-track.

Under the hood, The Little Engine That Could is a book about engineering management.

The clown is good at his job, too. Indefatigable. Persuasive. Throughout the day, he hails not one, but four engines that pass by throughout the book. Each time, he gets his team to amplify the case. Here he is calling out to the Passenger Engine:

So all the dolls and toys cried out together: “Please, Shiny New Engine, please carry our train over the mountain. Our engine has broken down, and the boys and girls on the other side will have no toys to play with and no wholesome food to eat unless you help us.”

See how the clown grounds his demand in a compelling user story. It’s not about schedules, commitments, expired food, committed capital, the exchange of money, nor about the golden rule. It’s about the children.

This moral turn makes the clown more of a preacher than a simple project lead or salesman. Everyone believes in their mission; the dolls and toys wail as they plead for help. But the Passenger Engine does not is too proud to heed the call — “I pull the likes of you? I think not!” — the Freight Engine too strong, the Old Engine too frail.

The Little Blue Engine gets on board, though. She sees an opportunity for herself: “I’m a little engine. They use me only for switching trains in the yard.” But what if…!

The clown’s tale opens up the possibility that the engine could be something more, and he provides the real-world directives for her to achieve it. If she can, then everyone wins: the engine, the boys and girls, the toys, the clown — as well as the executives back in NYC who green-lighted the delivery.

That’s the shadow side of narratives: there’s always something left out. To pay attention to one thing is to ignore another. The story focuses the mind and obfuscates the rest.

Think of the children. Think of the deadline. Think of your potential.

The proselytizing clown starkly contrasts with the massive engines — world framers and world-movers — but the distinction is perfect. Clowns are spiritually deformed. They are in the world but no longer of the world. Confer the Joker, Pennywise, Hop-Frog. Make a habit of shifting your perspective, of telling new stories, of juggling ideas, then your face turns white and your hair red.

Watty Piper knew this well, for Watty Piper himself is a fiction, a frame, a clown!

Piper is a pseudonym for the owner of the publishing company for The Little Engine. Like the unnamed clown elevating his practical needs to moral claims, the pseudonymous Piper weaves a story that seems lovely but is open to question. Was he writing for the children, or was he looking for ways to meet to keep the financial freight running on time?

“I thought I could, I thought I could, I thought I could,” the engine murmurs as it rolls down from its climactic success. It bought into the story and made it true. But it’s the funniest little manager you ever saw who is riding on top. He’s the one who will step off the track, shake hands with the parents, hand oranges to the grocers, and collect the paychecks — all for the children, of course.